(Please scroll down for the English version.)

木について語る:MoonRounds

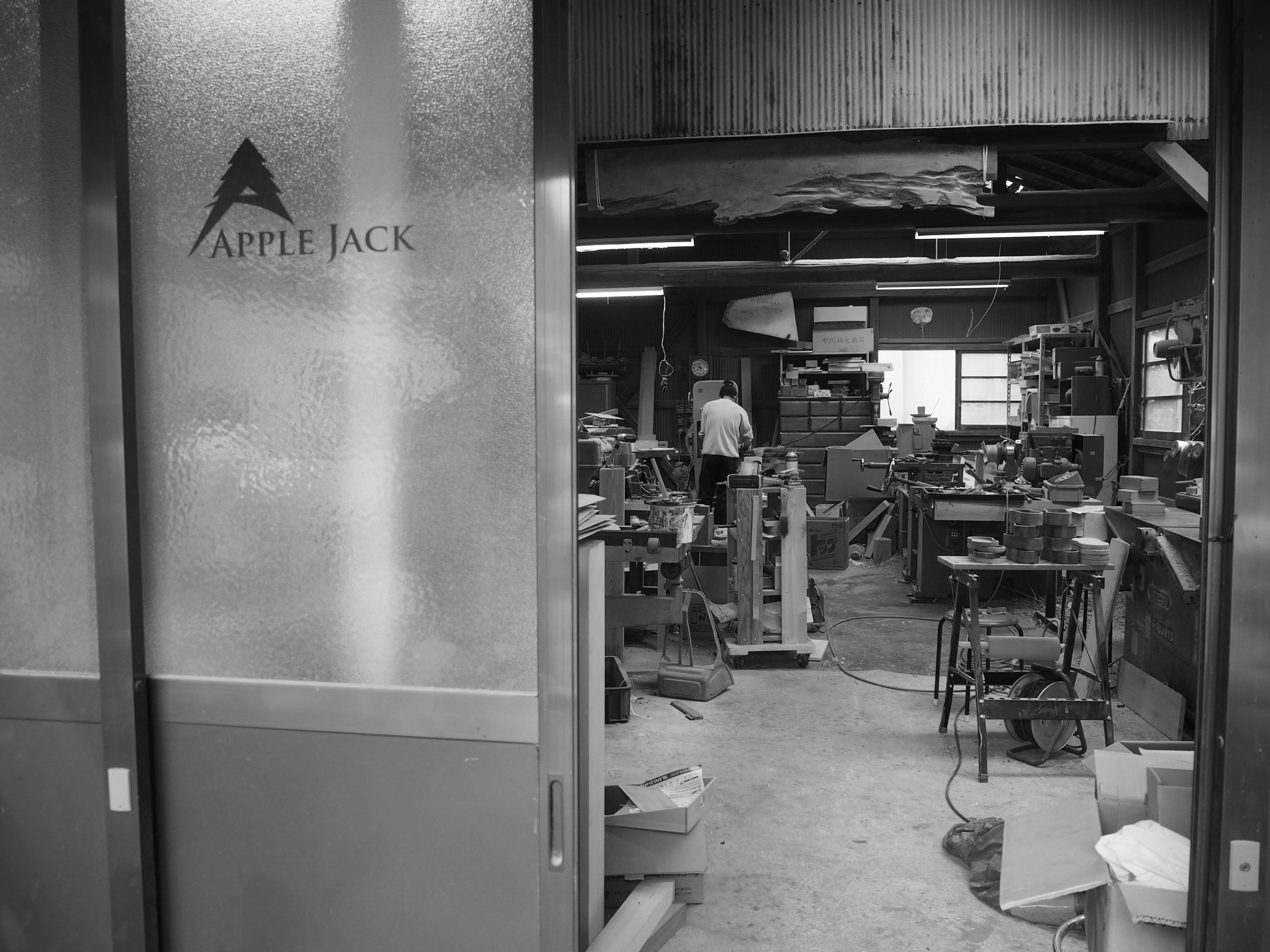

「満ち欠けする様にみえる自然のリズムに沿う」をイメージして、渡邉崇さんは自分の工房を「MoonRounds (ムーンラウンズ)」と名付けた。工房でろくろで木を回しながら、彼はお皿、茶碗、一輪挿しと他の「器」を作る。木工作家である崇は天然のオイルや草木で作品を染める。作品を見たら、一つ一つにストーリーがあると分かる。

「この間、台風で倒れた木や。」と崇さんは言い、県道を崩壊させた風倒木を指した。この分厚くて、300年生の杉の木は、吉野林業の長い歴史の証拠でありながら、自然と暮らす危険の証拠でもある。大きくなって、傾いてきて、倒れそうな街路樹もMoonRoundsの工房で並べてあった。何かとのゆかりがある木がよく崇さんの工房に届く。木に傷の跡や節や歪んだところがあっても、崇さんはそのいわゆる「欠点」を「特徴」として活かす。木の由来を暗示する特徴だ。それぞれの木は他の木と違う、独特の経験があると思い出させる特徴だ。

もちろん崇さんは傷のない、節のない木も使う。吉野杉、吉野ヒノキ、桜、栃、楠の木の作品が棚で並んでいる。大きくて平らなお皿の年輪がだんだん溶けて、長い雲のように見える。一輪挿しの年輪が潮の干満のように優しく上下する。年輪に合わせた茶碗の縁が海辺を離れた長い波のように見える。冬目を数えなくても、MoonRoundsの作品を見ながら、生命の経過を感じる。作品を一つずつ作るための思い、木とともに生活してきた人間、地球とともに進化してきた木。時計で計れない生命の経過だ。日常用品ではなくても、こんな作品と暮らすことはその生命の恩返しだ。

MoonRoundsの工房の上に弥勒寺というお寺がある。崇さんは木工の腕を貸して、近所の方々と一緒に弥勒寺を改装している。年に数回みんなで「弥勒茶屋」を開催する。近所の方は弥勒寺の歴史を調べて、参加者のための資料を作る。崇さんの奥さんは身内の冗談を交えた落語をする。座布団に座っている参加者は柿の葉寿司を齧りながら、笑い合う。この環境がMoonRoundsの作品に写っていると僕は思う。みんなの独特の力で成り立っている弥勒茶屋。木や草木の自然な模様と色彩を活かすMoonRounds。どちらにも人を受け入れる暖かみがある。どちらからも、自然のリズムに沿った暮らしの魅力がにじみ出る。

Talk On Wood: MoonRounds

In an image “along the waxing and waning rhythm of nature”, Takashi Watanabe named his studio “MoonRounds”. While spinning his lathe in his studio, Takashi makes plates, bowls, vases, and other “vessels”. As a woodworking artist, he dyes his works with natural oils and grasses. When you look at his works, you can see there is a story in each one.

“This is the tree that fell in the last typhoon,” Takashi said, pointing to the fallen tree that collapsed the prefectural road. This thick, 300-year-old cedar was both evidence of the long history of Yoshino forestry, as well as the danger of living with nature. A street tree that was chopped because it grew too large and was about to fall was also lined up in the MoonRounds studio. Trees with a connection to something often arrive at Takashi’s studio. Even with scars or knots or deformations, Takashi brings those so-called “flaws” to life as “characteristics”. Characteristics that suggest the history of a tree. Characteristics that remind us that every tree has had a different, unique experience.

Of course, Takashi also uses trees with no scars or knots too. Works made of Yoshino cedar, Yoshino cypress, cherry tree, horse chestnut, and camphor tree are lined up on his shelves. The year rings on a large flat plate gradually melt into what looks like a long cloud on the plate. The year rings on a vase softly ebb and flow like the tide. The lip of a bowl cut inline with the year rings looks like a long wave far away from the shore. Even without counting the winter rings, I feel the course of life while looking at the works of MoonRounds. The thought that goes into creating each work, the people who have lived with the trees, the trees that have evolved with the earth. It is the passing of life that cannot be measured by a clock. Even if it is not something you use everyday, living with these kinds of works is a way to say thank you for that time.

Above the MoonRounds studio is a temple called Miroku-ji. Takashi lends his woodworking abilities to help renovate it with his neighbors. A few times a year, they hold an event called “Miroku Tea House”. A neighbor researches the history of Miroku-ji and makes pamphlets for the participants. Takashi’s wife performs rakugo storytelling, throwing in inside jokes for locals. Participants sit on floor pillows while munching on persimmon leaf sushi and laughing together. I feel like this environment is evident in the work of MoonRounds. Miroku Tea House, formed via everyone’s unique skills. MoonRounds, bringing to life the natural patterns and colors of trees and grass. Both of them have a warmth that brings people in. From both of them emanates the beauty of a lifestyle along the rhythm of nature.